Does a Construction Cartel Explain Rising Rents?

To a man with an antitrust hammer, everything looks like a monopoly nail. In a recent Substack, antimonopoly campaigner Matt Stoller blames the rise in rents and anemic housing supply growth since 2007 on growing concentration in the home-building industry, rather than local land-use regulations, an explanation he attributes to “noisy” YIMBYs. Is he right?

Let’s start with what he is right about. A number of markets have seen growing concentration in the home-building industry since 2007. But this trend is a result of conscious government policy in the wake of the financial crisis to regulate mortgage lending more tightly, as Kevin Erdmann at the Mercatus Center has ably documented. These policies drove many builders out of business. Erdmann’s work, which is fully consistent with the work done in the 1990s and early 2000s by Ed Glaeser at Harvard, Raven Saks Molloy at the Fed, Joseph Gyourko at Penn, and Bill Fischel at Dartmouth, among many others, shows that the housing shortage predates 2007, at least in many markets. Indeed, tight zoning rules have been fingered as a cause of costly, scarce housing since at least 1972.

The rise in builder concentration is a more recent phenomenon, which is not good news for the thesis that builder concentration has driven growth in rents. But Stoller has one other piece of evidence: builders’ use of “land banks” to acquire lots and hold them for later development. He calls this evidence of cartel behavior:

Interestingly, I suspect there’s a cartelization effect going on as well. Here’s Toll Brothers CEO Doug Yearley a few years ago:

‘We’re doing significantly more third-party land banking where we assign a contract to a professional land banker, who then feeds us land back on an as-needed basis,” Yearley said. “And then, we’re doing joint ventures with either Wall Street private equity or with our friends in the home building industry, the other builders.’ (emphasis original)

What exactly does that quote mean? I don’t know, but it seems kind of crazy that large homebuilders would be doing joint ventures with each other on land acquisition, when that could very easily lead to holding supply off the market and preventing smaller developers from competing to build cheaper homes.

But neither “land banking” nor joint ventures are evidence of cartel behavior (intentionally withholding lots from development in order to drive up new housing prices and profits). Land development is an incredibly risky business. You have to try to gauge what market conditions will be in a couple of years once your permit approvals have come through and the new units are move-in ready, but meanwhile you’re taking on large debts that you have to start paying back immediately. It makes sense not to develop every plot of land you own instantly, while you observe the vicissitudes of the real-estate market and, if necessary, ride out a bad patch. For the same reason, it can make sense to spread risk across multiple financial partners who all share a long-term view.

Stoller cites a working paper by Johns Hopkins University economist Luis Quintero as evidence that market concentration in home-building is driving up housing costs. It’s a serious paper, but it also has some methodological limitations, which may explain why it has apparently kicked around for seven years without yet passing peer review. (It focuses on just a few East Coast markets, it defines housing markets in an unusually narrow way, and the instrument seems to be valid only under the condition that it mostly just captures time trends, not cross-section variation, but then there could be many omitted factors that share a similar time trend.) Quintero may well be right that home-builder concentration does reduce housing supply and raise costs, but it hasn’t been proven yet, and it’s at best a minor factor compared to the zoning restrictions YIMBYs talk about.

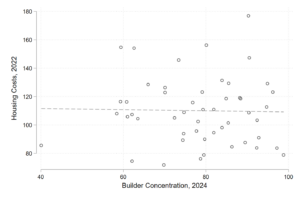

As a way to visualize the debate, I looked at the source Stoller uses for builder concentration data (the share of the market controlled by the top 10). Then for each of these markets, I plotted the relationship with the most recent housing costs measure (“regional price parities”) produced by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The result is below.

The relationship between builder concentration and housing costs in these 50 markets is zero, completely flat. Now, maybe you can construct a fancy causal model in which you can tease out some small positive effect once you control for X, Y, and Z or net out some kind of reverse causation, but this plot should give us a strong suspicion that builder concentration cannot be more than a distant secondary or tertiary explanation for why some markets are more costly than others.

As an example, the Cincinnati metro area is one of the most highly concentrated markets (97.2 percent market share for the top 10 builders!), but one of the cheapest places for housing (83.7 percent of the national average!). Seattle is not concentrated at all (59.4 percent top 10 share), but is quite expensive (154.8 percent of the US average).

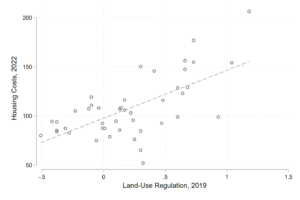

Now what happens when we plot housing costs in 2022 against the most commonly used measure of local residential land-use regulation? You get this:

Now that’s a strong correlation! You can quibble with the causal story here: maybe high-demand markets tend to see housing costs rise and also try to adopt more regulation, but even these alternative stories still end up affirming an effect of regulation on housing costs. High-demand areas regulate supply to protect values for incumbent homeowners.

Not every problem in the American economy is about lack of competition, and not every policy “solution” aimed at this non-problem will make things better. Stoller’s proposal to equalize credit costs between big and small builders will probably just cause everyone’s credit costs to go up. Big builders are better risks, so financiers will reduce lending if forced to lend at the same rates to big and small builders. More costly financing means… less building and more costly housing. Instead, let’s listen to the YIMBYs and legalize building in high-demand areas.

This piece originally was published by the American Institute for Economic Research.