The Top 5 Most Misunderstood Economic Concepts

For all the attention given to economics by mainstream media and political pundits, our economic literacy as a society still leaves much to be desired. We opine on economic issues constantly, we deliver passionate soliloquies defending our partisan viewpoints, but rare is the occasion when we sit down and actually try to learn economics.

The result of this disparity between attention and education has been the emergence of a number of economic fallacies, misunderstandings, and leaps of logic. People repeat economic ideas because they sound like common sense, even when these ideas have been debunked time and again by those who have thought about them a bit more carefully.

Many volumes could be written on the common economic misunderstandings that plague our society. But for the sake of, well, economy, we will have to pick only the most prevalent of these missteps for the following analysis. To that end, here is my selection for the top five most misunderstood concepts in economics.

1) Scarcity

The concept of scarcity seems pretty straightforward: we have virtually unlimited wants, and yet we live in a world where the means for satisfying these wants are limited. There are only so many cars, computers, homes, factories, doctors, and so on. Devoting more of these resources to one end means devoting fewer of these resources to other ends.

Simple as this may seem, there are many who maintain that scarcity is only a fact of life because of the economic system we live under. If we had a better economic system, they say, scarcity would no longer be a problem.

The economist Ludwig von Mises drew attention to this view in his 1949 economic treatise Human Action:

He who contests the existence of economics virtually denies that man’s well-being is disturbed by any scarcity of external factors. Everybody, he implies, could enjoy the perfect satisfaction of all his wishes, provided a reform succeeds in overcoming certain obstacles brought about by inappropriate man-made institutions. Nature is open-handed, it lavishly loads mankind with presents. Conditions could be paradisiac for an indefinite number of people. Scarcity is an artificial product of established practices. The abolition of such practices would result in abundance.

After discussing the historical development of this position, Mises gives his take on the matter, leaving no doubts as to where he stands:

Such is the myth of potential plenty and abundance. Economics may leave it to the historians and psychologists to explain the popularity of this kind of wishful thinking and indulgence in daydreams. All that economics has to say about such idle talk is that economics deals with the problems man has to face on account of the fact that his life is conditioned by natural factors. It deals with action, i.e., with the conscious endeavors to remove as far as possible felt uneasiness. It has nothing to assert with regard to the state of affairs in an unrealizable and for human reason even inconceivable universe of unlimited opportunities.

2) Greed

Another economic concept that is highly misunderstood is greed. Specifically, many people seem to believe that prices and wages are determined by how greedy a business is. Higher prices for consumer goods and lower wages are, in this view, a result of increased greed.

But this makes no sense, because businesses were presumably just as self-interested before the changes as after. “Blaming rising prices on profit-seeking is like blaming a plane crash on gravity,” writes Dan Sanchez:

Gravity is always pulling down on planes. To explain a plane crash, you have to explain what happened to the factors that had previously counteracted that downward pull. Why did gravity yank the plane down to earth when it did and not before?

Similarly, businesses are always seeking profit and are always ready to raise prices if that is what will maximize profits. To explain precipitous price hikes, you have to explain what happened to the factors that had previously put a lid on that upward price pressure. Why did profit-seeking propel prices skyward recently [in 2022] and not in 2019?

It’s certainly true that self-interest is part of the economy. But it makes no sense to explain price changes by referring to avarice.

3) Economic Growth

Sir David Attenborough expressed a very popular sentiment when he said in 2013: “We have a finite environment—the planet. Anyone who thinks that you can have infinite growth in a finite environment is either a madman or an economist.”

The problem with this thinking is that it completely misconstrues the concept of growth in economics.

“By growth, economists mean value-creation exchanged in the marketplace,” writes Joakim Book. Once we understand the economic perspective, it becomes clear that growth in this sense can be practically infinite, even in a world of limited physical resources.

“Although we live in a world of a limited number of atoms,” write Marian Tupy and Gale Pooley in their 2022 book Superabundance, “there are virtually infinite ways to arrange those atoms. The possibilities for creating new value are thus immense.”

As Tim Worstall writes, “GDP is not minerals—or anything else physical—processed. It’s value added. The limit to GDP is therefore in knowing how to add value. Therefore, while physical resources are obviously scarce—there’d be no subject called economics if that were not so—it is not physical resources which limit economic growth. It’s knowledge.”

4) Public Goods

For many people, a “public good” is any good which is provided by the public sector, that is, the government. Thus, people consider roads, utilities, and other public services to be public goods.

But this is actually incorrect. There is a strict definition of “public good” in economic theory, and it has nothing to do with whether something is provided by the government.

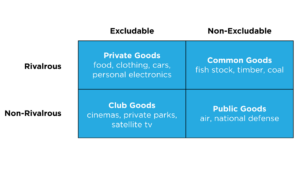

Economists often classify goods based on two factors, their rivalrousness and their excludability. A rivalrous good is a good for which one person’s use gets in the way of another person’s use. For example, food would be rivalrous (we can’t both eat the same food), whereas satellite radio would be non-rivalrous (my consumption of it doesn’t take away from your ability to consume it as well).

Excludability refers to how easily a nonpayer can be excluded from consuming the good. Computers would be excludable, because it’s fairly straightforward to prevent nonpayers from accessing them. But something like asteroid deflection would be considered non-excludable, because it’s much harder to restrict the benefits to only those who paid for it.

With these two classifications in mind, economists have come up with a 2×2 grid that contains four categories: private goods, common goods, club goods, and public goods. A public good, by definition, is a good that is both non-rivalrous and non-excludable.

Alex Tabarrok sets the record straight in his discussion on public goods:

A public good, as we’ve said, is a good which is non-excludable and non-rival. A public good is not defined as a good that is produced by the government, or the public sector. After all, if the government started to produce jeans, that would not make jeans a public good. Mail delivery is provided by the government, but it’s not a public good. Asteroid deflection is a public good, but actually very little of it is provided by government.

Whether public goods should be provided by the government—and if so, how much—is a topic of active debate. Some economists even dispute the utility and soundness of this whole classification approach. But all economists agree that the definition of a public good has nothing to do with whether a good is or is not currently provided by the government.

5) Capitalism

Capitalism is yet another concept that is seriously misunderstood by many people. Specifically, people often think that capitalism just means doing what’s good for big businesses. When the government interferes in the market to help large corporations, people say that this is capitalism in action.

But nothing could be further from the truth. Capitalism is an economic system characterized by private ownership of the means of production and free exchange with the goal of making profits. All government interference in the market involves coercion and is thus a move away from pure capitalism.

Supporters of capitalism believe the government should not protect businesses from competition in any way. It should not subsidize them or give them protective tariffs or bail them out. It shouldn’t regulate their industry. And it shouldn’t give tax advantages to some firms or sectors over others. True capitalism is not cronyism or corporatocracy, but the opposite. It is a system where competition is an ever-present threat to big businesses, where businesses are allowed to fail, and where special government privileges are absent.

“You must separate out being ‘pro-free enterprise’ from being ‘pro-business,’” said Milton Friedman. “The two greatest enemies of the free enterprise system in my opinion have been on the one hand my fellow intellectuals, and on the other, the big businessmen.”

After discussing the view of his fellow intellectuals, he elaborates on his point about big businessmen:

You cannot get a businessman on a podium… without them uttering generalities about the desirability of free enterprise systems. But when I come to their own business, that’s something else… Almost every businessman is in favor of free enterprise for everybody else, but special privilege and special government protection for himself. As a result, they have been a major force in undermining the free enterprise system… Stop kidding yourself into thinking you can use the business community as a way to promote free enterprise. Unfortunately, most of them are not our friends in that respect.

Government regulation is often desirable for specific big businesses, but it is bad for both business and consumers in general and is antithetical to genuine capitalism. When the government protects, subsidizes, or bails out large corporations, that is a move away from capitalism, not an example of how capitalism operates.

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kB2gBgsqPac&t=2s

Moving Beyond Bad Ideas

The reason that economic fallacies such as these persist is because of a scarcity problem: a scarcity of economic literacy. As a society, we have not taken the time to understand the economic concepts we debate. We have not done our homework, and the result is that we repeat over and over again the same bad talking points and ideas.

But all hope is not lost. By committing to improve our economic understanding, we can level up our economic dialogues and have debates that are more informed. We can move the conversation beyond debunking common fallacies and toward a genuine exchange of ideas.

The only question is: are we willing to put in the work?

This piece originally was published by the Foundation for Economic Education.